https://educationcommission.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Education-for...

https://www.bcg.com/publications/2022/fostering-green-skills-to-accelera...

Before the pandemic, it was estimated that by the end of this decade, half of the world’s young people would finish their education without the most basic secondary level skills.This generation will need to move into greener jobs and adapt to complex environmental and societal problems, so it’s urgent the educational community acts now. We must break down silos across education and climate spaces and

explore win-win solutions that put the health of the planet and wellbeing of people at the center. The approach presented in this paper is a first step in this direction.

More than 130 countries are aiming for net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. Technological innovations will be critical to reaching this goal, but achieving and sustaining net zero also require learning how to live on this planet as the climate rapidly changes—and education is a key enabler of this transition.

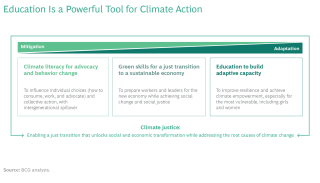

Education is a powerful means of developing the climate literacy that behavioral change and collective action require. It can also cultivate green skills and help ensure a “just transition” to a sustainable economy so that no group is left behind. Finally, education can build the adaptive capacity and resilience of communities. While there has been some momentum in each of these areas, more funding and greater scale and coordination of activities are needed.

We believe that education—often overlooked as a factor in reaching these goals—must become a more central theme in climate discussions and that the education sector needs to ratchet up its own ambitions to spur climate justice. (See the exhibit.) There is no time to waste.

Behavioral change at the individual and household level—in choosing modes of travel, what to eat and drink, and how to heat and cool one's home, for instance—can contribute meaningfully to holding global warming to 1.5° C above preindustrial levels. And education can help spur those changes. By increasing students’ awareness and understanding of climate change and climate action, schools can empower young people to become agents of change in their local communities, instilling new norms and inspiring a sense of the possible. Early studies suggest that once young people become climate literate they help educate their families, which has a multiplier effect on their communities. To accelerate climate literacy, educators, educational institutions, and governments must commit to implementing curricula that are action oriented (as opposed to merely being disseminators of information) and to training teachers accordingly. For example, the Green Schools Programme in India empowers teachers and students to deploy climate action projects in their local communities; elsewhere, Italy and New Zealand (and soon, Mexico) have committed to formally integrating climate literacy into national curricular requirements. In parallel, schools must invest in greening their own infrastructure (from transportation to meals to energy use) so that they can lead by example while offering experiential learning opportunities for students. Organizations such as UndauntedK12, Let’s Go Zero, and the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education are working to encourage climate-friendly school infrastructure in the US and UK—and these are just a few examples. Researchers should also rigorously evaluate the spillover effects that developing climate literacy has on the broader community in terms of advocacy and behavior change. More research is needed, but early studies suggest that school districts are near optimal size to scale climate action at the local level, making them a potent tool for broader community engagement and empowerment. As economies transition from "brown" to "green," education can equip today's workers through reskilling and continuing education while laying the groundwork for those who will fill (and define) the jobs of tomorrow. This is critical, for without the skilled workers needed to scale innovations, the transition to a green economy could be delayed (the current shortage of qualified wind turbine technicians is an example). The stakes are high. A just transition—which ensures that no group is left behind or left to shoulder an unfair burden—could deliver millions of new jobs in sustainable economies. Failure, on the other hand, could result in structural unemployment, undermining public support for climate action and fomenting social unrest. In fact, it is estimated that without reskilling, nearly 77 million jobs could be at risk globally—although that risk will vary significantly by industry and geography. Moreover, it’s important to remember that reskilling is critical not just to developing the skills needed for green jobs (such as in green energy) but also to ensuring that displaced workers acquire skills that will be useful elsewhere in a greener economy. Finally, this transition is an opportunity to ensure that those shut out of particular jobs because of gender bias or disability, for example, are included in the development of a more diverse, inclusive, and equitable workforce. To facilitate a just transition to a sustainable economy, education, government, and industry leaders must adopt an expansive view of green skills and climate literacy that includes both the technical and the leadership skills that the future demands. Leaders need to take a data-driven approach to understanding the skill requirements of a greener economy and align educational programs and training institutions accordingly. Partnerships among education, government, and industry need to focus on ensuring that everyone, especially those from historically marginalized groups, has the necessary skills and pathways to a good job. Take, for example, the Greater Houston Partnership’s Energy Transition Initiative, which is proactively assessing the green-skills gap and working to ensure that the local education system is prepared to fill it. South Africa’s National Business Initiative has likewise worked to map sector-by-sector requirements (in the power, mining, petrochemical, and other industries) for a just transition, the impacts on jobs, and the reskilling programs required. Although the specifics of each industry and region’s transition will differ, stakeholders can and must learn from each other as they seek to tackle this challenge. To date, many investments to improve adaptability and resilience have focused on infrastructure. But given unpredictable climate patterns, these investments could lock countries into strategies for coping with climate change that prove insufficient. We believe that greater investment in education, especially for girls and women, is a critical means of enhancing adaptive capacities over the long term. Women are often closest to many of the key levers for climate-related behavioral changes, such as in water usage, farming techniques, and cooking and heating habits. Investments in women’s and girls’ education offer the potential dual benefit of furthering climate action while increasing overall social equity. In fact, one study projects a 60% lower death toll from extreme weather events between 2040 and 2050 if 70% of women in Sub-Saharan Africa receive a secondary-school education.1 Improvements in adaptive capacity are possible even when education does not explicitly address climate topics. Through increased literacy and economic opportunity, vulnerable populations are better equipped to respond to climate-related challenges, such as floods that force them to move or poor harvests that require them to find other work. Some organizations have begun to recognize this correlation, such as the Campaign for Female Education (Camfed) and the Green Climate Fund, which is funding Save the Children’s educational work. To build a stronger case for educational investment, more research is needed to demonstrate the link between education and improved adaptability, resiliency, and economic opportunity. Increased evidence for and awareness of education's potential could strengthen countries’ National Adaptation Plans and unlock more flexible intersectional funding. Education can have a transformative impact on climate action. It empowers students to reduce and respond to the adverse effects of climate change and to bring what they learn in the classroom to their communities. It gives workers the skills necessary to thrive in a green economy. It equips leaders to implement the next tier of climate innovations and to navigate a just transition. And it enables citizens to use their voice, consumer power, and political support to drive climate action. The time is now to unleash the power of education in promoting climate action and justice. To learn more about the power of education in climate action and justice, see our full report, Education for Climate Action. "Climate change is “widespread, rapid, and intensifying,” and without urgent action the world could hit a tipping point from which there is no return. That was the assessment of last year’s report from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which also left little room for doubt that human actions, even at the very local level, will determine the future course of climate change1 . Last year’s COP26 climate meetings instilled some hope that it’s possible to avert the worst effects of climate change. The Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) unveiled during the talks-as well as sector goals-could deliver some of the emission reductions required to limit global warming. It was also encouraging that issues of adaptation, loss, and damage among low-income countries received more attention, although disappointing that developed countries fell short of the $100 billion of monetary support that they had pledged2 . Also notable at COP26 was the growing and increasingly vocal youth movement calling on leaders to be more ambitious.3 Strangely, however, relatively little attention has been paid to how education can improve climate literacy, encourage behavioral change and be a critical part of other systemic climate-related initiatives. We believe that education must become a more central theme in the climate dialogues and the education sector needs to ratchet up its own ambitions to be part of the solution. While the push to teach climate literacy in schools has been gaining traction, with many new and established organizations devoted entirely to this goal, a more concerted effort is needed to make education part of every country’s climate strategy; that includes mobilizing high-level political support. Education has not been prioritized as a solution to the climate crisis, yet we believe it is critical to reaching long-term mitigation and adaptation goals. Over 130 countries have targeted reaching net zero by 2050,9 which will require halving emissions each decade in the 2020s, 2030s and 2040s.10 While technological innovations are an important lever to accomplish this goal, especially for the first halving of emissions, reaching and sustaining net zero on the path to 1.5°C also requires relearning how to live on this planet and with each other, recognizing that our climate is already rapidly changing. We see three primary areas where education can play a major role addressing the climate crisis. While there is some momentum in each of these three areas, more is needed to meet the moment, including greater coordination, scale of activity, and funding. Teaching climate literacy for behavior change & collective action: Some estimate that as much as ~20-37% (~390-730 GT) of the emissions reduction needed to achieve net zero depends on individual and household behavior change.11 Reaching a 1.5°C world calls for a climate literate population; yet only three countries have formally integrated climate literacy into their curricula.12 This leaves the majority of teachers and students with a patchwork of resources for climate action, despite increasing calls for support by activists, teachers’ unions, and students themselves.13 Inspiring behavior change among students and making them agents of change will require a deep commitment to robust, action-oriented, empowering programming as opposed to mere ‘information dissemination’ about climate change and action. Moreover, teachers will need quality training and support to implement the curricula. Cultivating skills for a “just transition”14 to a green economy: New economies will require transformative green skills, new forms of leadership and the re-skilling of those in impacted industries as well as communities that have historically endured social marginalization, including women and girls. In other words, these transition efforts should emphasize justice and equity, ensuring that barriers to entry, success, and leadership are eliminated, including harmful gender norms, structural racism, economic discrimination, and inequitable workplace policies. Handled correctly, this transition could deliver millions of new jobs in sustainable economies,15 while failure could result in mass structural unemployment, undermining public support for climate action. Yet fewer than 40% of NDCs reference skills training, and 1 in 5 have no plans for training or capacity development at all.16 Plans that do exist are often reactive rather than proactive, focusing narrowly on retraining for displaced workers rather than the transformative leadership skills needed at all levels of organizations and communities. Too narrow a focus on technical skills also risks reinforcing the gendered nature of our current economy, and risks reinforcing a status quo where women and girls are excluded from economic opportunity. Teaching the technical and transformative skills needed for an equitable green transition will require significant investment from both domestic budgets and development financing. For the greatest impact, these efforts should be in partnership with the private sector, trade unions and civil society, and guided by the principles of justice, equity, and inclusion – when done well, such partnerships can offer win-wins that deliver more equitable education and employment at the same time as they further a green economic agenda. Building the capacity to adapt: Education is strongly connected to a person’s ability to adapt to changing circumstances – something that will be crucial for society as the effects of climate change intensify. But populations most vulnerable to climate change today are often those in developing countries with the least access to education-the majority of whom are women and girls. Improving access to education that builds adaptive capacity and removes barriers to empowerment is critical to building climate resilience. Moreover, schools that adapt themselves to be more resilient could provide protection, shelter in case of disaster, ensure food security through school meals and other support, bolster mental health and resilience, and help build the future workforce.

Developing Climate Literacy

WHAT’S NEEDED?

Cultivating Skills for a Just Transition

WHAT’S NEEDED?

Building the Capacity to Adapt

WHAT’S NEEDED?

Add new comment