https://globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/land-and-environmental-defenders/...

By Nonhle Mbuthuma

We will not be silenced. We will keep making history

It was like a bomb had been dropped on us. We had just learned that the petrochemical giant Shell was looking for oil and gas off the coast of South Africa, close to where I live. Not that anyone had bothered to inform us – not our government, not Shell, not anyone else. We heard it in the news.

Little did it matter that our Constitution clearly states that we must be consulted. Like so many other land and environmental defenders around the world, we found our basic rights violated. Yet I count myself lucky because I am here to tell my story.

As this new report documents, 196 fellow defenders can’t tell their stories; they were brutally murdered in 2023.

This report shows that in every region of the world, people who speak out and call attention to the harm caused by extractive industries – like deforestation, pollution and land grabbing – face violence, discrimination and threats.

We are land and environmental defenders. And when we speak up many of us are attacked for doing so.

South Africa’s marine environments are stunning. Like many peoples and cultures worldwide, the Indigenous Peoples of the Eastern Cape find solace and leisure in our oceans.

But to us, they are more than sandy shores and turquoise waters. They are a vital food source and a lifeline for millions of people. They are home to many endemic marine species. They are sacred places, with deep cultural meaning that stretches back generations.

Shell’s seismic exploration rights were revoked and ruled unlawful by a South African court in September 2022, following a campaign by residents. Rogan Ward / Reuters

Imagine, then, how I felt when I learned that Shell was going to carry out months of seismic blasting – an activity as bad as it sounds – in biodiverse coastal waters near my home.

The blasting zone in Maputaland-Pondoland, Albany, would cover 6,000 square kilometres – two and a half times the size of Cape Town. Shell’s path to further oil and gas extraction would not only be catastrophic for marine life, but also for people and for our planet.

This is when I understood how invisible we were and just how little companies like Shell care about their impact on the climate, pollution, and biodiversity – collectively, the greatest human rights challenge of our generation.

The breach of these fundamental rights by governments and companies in pursuit of profit is not just minor collateral damage. Their actions have life-changing consequences for us all.

Like many communities facing environmentally destructive projects on their doorstep, we knew the only way forward was to build a movement across South Africa.

The breach of these fundamental rights by governments and companies in pursuit of profit is not just minor collateral damage. Their actions have life-changing consequences for us all

Together, ordinary people – including families, activists, journalists, lawyers – worked to show our government that there is another, more equitable path to power the future. Our message resonated beyond our coastal towns, and our movement quickly swept across the world.

We were up against a multinational company and a government that had been supportive of its plans. Regardless, we took Shell and our government to court. And our perseverance and determination paid off.

In September 2022, the Eastern Cape Division of the High Court of South Africa revoked Shell’s exploration rights and ruled that conducting seismic surveys on the Wild Coast of South Africa was unlawful.

This was a landmark decision and a historic win for us. We felt vindicated. But our joy was short-lived. The judgement was quickly appealed, and we are waiting to learn the date of the next hearing.

Whenever it may be, we’re ready.

Nonhle Mbuthuma, a 2024 Goldman Prize Winner and founder of the Amadiba Crisis Committee, leads the amaMpondo community in South Africa. Thom Pierce / Guardian / Global Witness / UN Environment

Being an environmental defender does not come without personal sacrifice. Decades of working to protect our planet have taken a toll on me physically and emotionally. There is a hidden cost to our activism.

For years, I have faced death threats, brutality, criminalisation and harassment. Knowing my life is in danger every day is deeply taxing. And I know I am not alone.

Since Global Witness started reporting on killings in 2012, over 2,000 defenders around the world have been murdered. Yet governments fail to document and investigate attacks, let alone identify and tackle the root of the problem.

Defenders and their communities are exposed to an ever-evolving range of reprisals, many of which are hidden from view. Or worse, ignored.

When I look at my country, so rich in resources yet so unequal, I can clearly see that natural resource extraction is oppressing rather than supporting citizens. The exploitation of people and the environment has its roots in colonial violence, racism, and injustice.

Our ancestors understood the power of informing, educating, and mobilising people. And they made history by putting such power to use.

Knowing my life is in danger every day is deeply taxing. And I know I am not alone

Now it is my role, as a defender, to push elite power to take radical action that swings us away from fossil fuels and towards systems that benefit the whole of society.

It is the job of leaders to listen and make sure that defenders can speak out without risk. This is the responsibility of all wealthy and resource-rich countries across the planet.

So, every time I am told about the benefits of multinational corporations operating in my country, I always ask: once the ocean has been polluted, once our livelihoods have been destroyed and the inequality gap widened, once irreversible damage has been done, who is going to pay the price?

Today, we are in a climate emergency. And in many ways, we’re still having to fight for the same basic things: our fundamental rights. Defying this status quo is a collective challenge for our future and for the future of our shared world.

That is precisely why we will keep fighting. It is why we will not be silenced. It is why we will keep making history.

Recommendations

Recommendations: EU and US – September 2024

Uncovering reprisal trends: How states and business can better protect defenders

Global Witness reports each year on killings of land and environmental defenders around the world. This year’s report, which contains data from 2023, also illustrates the many ways in which attacks against defenders remain hidden.

The causes of reprisals are firmly anchored in specific country contexts and influenced by local power dynamics that determine who can speak up for defenders’ rights.

To protect defenders, we need countries to systematically document attacks and reprisals. New and better data on these attacks and their causes would enable governments to improve existing laws and mechanisms. Given the limited progress made so far, we need urgent acceleration.

Legally binding mechanisms like the Escazú Agreement in Latin America require governments to guarantee access to information, public participation and justice.

But globally, governments and the companies that operate within their borders must do more to bring to light attacks against defenders and their communities, and put an end to the violence.

Governments and companies must also be held to account for the violence and criminalisation that land and environmental defenders face around the world.

The following global recommendations need to be tailored to the specific circumstances and political context of individual countries.

Thousands gather at the Acampamento Terra Livre (Free Land Camp) as part of a major annual mobilisation to amplify the voices and resistance of Indigenous peoples in Brazil. Cícero Pedrosa Neto / Global Witness

Governments and states should:

Create a safe environment for land and environmental defenders

Defenders should be able to freely exercise their roles without fearing for their lives. Existing laws and mechanisms that protect and recognise defenders – while tackling the causes of attacks against them – need to be prioritised and enforced.

Examples include the Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters under the Aarhus Convention, the Escazú Agreement, the UN Special Rapporteur procedures and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Where such laws and policies do not exist, new binding instruments and frameworks should be established in collaboration with rights holders and experts.

Escazú-inspired regional agreements could be established in Africa and Asia – there are already efforts underway to create a regional legal instrument that will uphold and strengthen people’s environmental rights in ASEAN countries.

All relevant information should be made accessible to communities and stakeholders to give them a genuine role in making decisions about land and natural resources.

New laws should include safeguards to prevent their misuse as tools to criminalise defenders. Existing laws that specifically target or criminalise defenders or protestors should be revoked.

Systematically identify, document, and analyse attacks against land and environmental defenders

To be effective, legislation and public policies to protect defenders need to be based on a deep understanding of the realities and challenges that defenders face. It is therefore essential that governments collect data on reprisals against defenders.

Data gathering must be transparent and participatory; it is often defenders themselves that have the most detailed information on reprisals. Data must also be collected in line with governments’ commitments to the Sustainable Development Goals.

Where possible, this should include data broken down to reveal any violence faced by vulnerable groups such as Indigenous Peoples, women and girls, and land and environmental defenders.

Systems to document reprisals should also incorporate effective monitoring, including monitoring of civic space where it is compromised and monitoring of impunity linked to attacks against defenders, which would help to disincentivise attacks and establish effective remedies for reprisals.

Facilitate access to justice

As long as reprisals against defenders remain unpunished, they are likely to continue. That is why it is essential that defenders have access to an impartial and non-discriminatory justice system and that their fundamental rights are upheld.

That includes universal rights to free, prior and informed consent; Indigenous Peoples’ rights to their livelihood and culture; the right to life, liberty and freedom of expression; and the right to a safe, healthy and sustainable environment.

These rights are already embodied in various national and regional laws, and non-binding international resolutions.

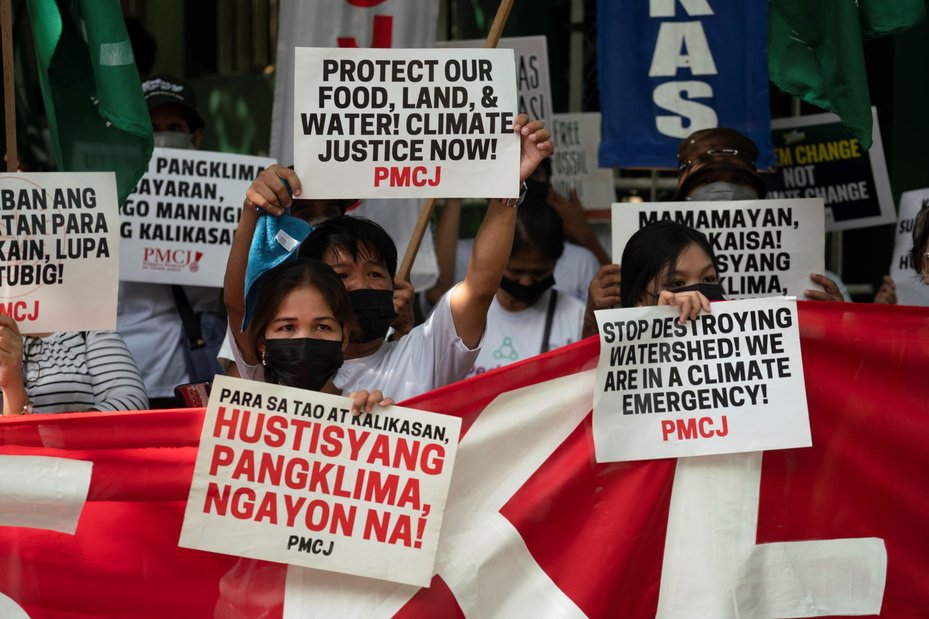

Volunteers from the Philippine Movement for Climate Justice gathered at the Department of Environment and Natural Resources and called on the government to declare a climate emergency. Quezon City, Philippines, July 2022. Rajiv Villaber / Global Witness

Businesses should:

Systematically identify, prevent, document, mitigate and remedy harm caused to defenders in their operations

Businesses must implement robust procedures that identify, prevent, mitigate and remedy human rights and environmental harm throughout their operations, including undertaking due diligence on their entire supply and value chains.

They should use data on attacks, on trends affecting civic space and on key causes of harm as starting points to inform business decisions.

Businesses should take into account data collected by governments, independent institutions, civil society groups and defenders.

Businesses should also monitor cases of reprisals, identify systemic risks, and adapt relevant business activities following genuine stakeholder engagement.

Ensure legal compliance and corporate responsibility at all levels

Businesses must show zero tolerance for attacks and reprisals against land and environmental defenders, illegal land acquisition and violations of the right to free, prior and informed consent.

They should apply a zero tolerance policy at all levels of their operations. They should also identify clear red lines for prompt suspension or termination of contracts for non-compliant suppliers.

Social activist Rinchin has been a key figure in the "Save Chhattisgarh" movement in central India, supporting Indigenous Adivasi communities who face brutal repression for resisting large-scale mining developments. Ravi Mishra / Global Witness

Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Convention on Biological Diversity should:

Facilitate access and genuine participation of land and environmental defenders and their communities

The voices of defenders, their experiences and the challenges and risks they face must be front and centre in climate and biodiversity discussions and negotiations. This is particularly essential for Indigenous voices.

Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Convention on Biodiversity (CBD) should publicly recognise the crucial role that environmental defenders play in combatting climate change, conserving biodiversity, and protecting ecosystems.

Parties must unequivocally commit to fulfilling their human rights obligations under the United Nations Charter and international human rights law before, during, and after UNFCCC and CBD negotiations.

Participation of defenders and communities should directly inform global and national action under the UNFCCC and the CBD. Defenders must contribute to the design and realisation of plans to implement the Paris Agreement.

Examples of where this should happen are the development of national climate plans and the energy transition programmes. All should follow a human rights-based intersectional approach to climate action.

Parties to the UNFCCC and CBD should also ensure that Indigenous Peoples’ knowledge, experience and practices are taken into consideration in climate decision-making.

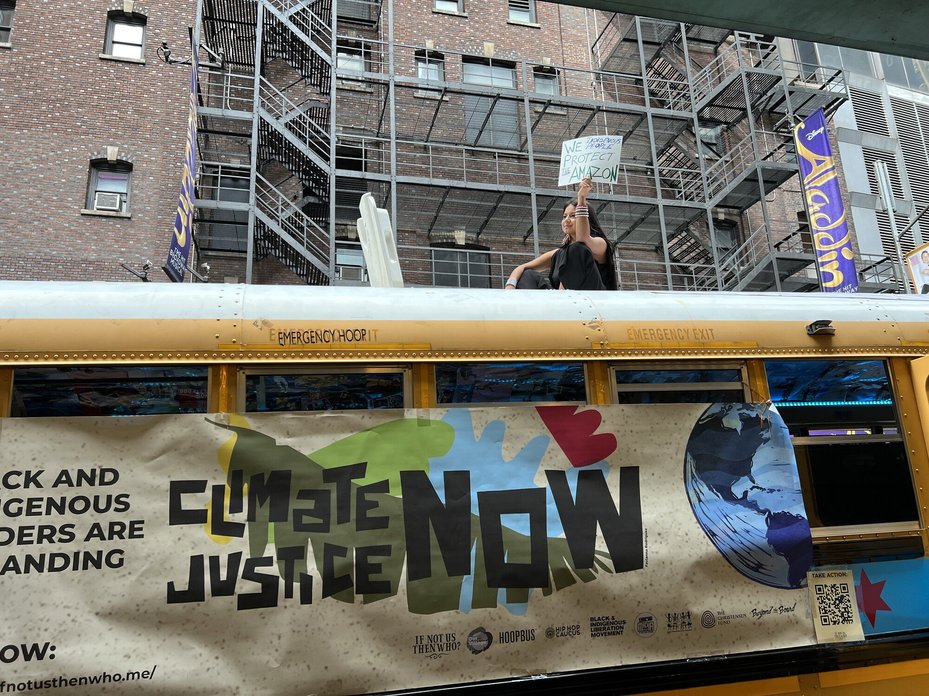

Helena Gualinga, an Indigenous activist from Ecuador, at the climate justice rally as part of New York Climate Week in September 2022. Caroline Challe / Global Witness

Regional recommendations

European Union

A new EU law called the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) makes it obligatory for large companies to conduct human rights and environmental due diligence across their global supply chains.

The CSDDD also gives communities and defenders the right to submit complaints and sue companies in EU courts if companies cause harm to people and the planet.

Tools embedded in the law could be transposed in a robust and ambitious manner to best protect and empower affected communities and defenders.

See our recommendations:

Regional recommendations

United States

The US has several legislative and policy tools that could effectively support the protection of defenders. These include the Guidelines for US Diplomatic Mission Support to Civil Society and Human Rights Defenders.

The Guidelines outline how US diplomatic missions should assist civil society organisations and human rights defenders.

These should be implemented, promoted and openly shared by the US government, and they should be periodically independently reviewed.

Another important tool is the Magnitsky Act, which can impose sanctions on foreign individuals responsible for human rights abuses or significant corruption, including individuals and entities responsible for committing violence against land and environmental defenders.

The US Congress should also introduce robust legislation in support of land and environmental defenders, such as the recently introduced Human Rights Defenders Protection Act.

It should also ensure that human right conditions are placed where security forces are engaged in egregious attacks against defenders.

See our recommendations:

Regional recommendations

Methodology

The Global Witness Land and Environmental Defenders Campaign aims to stop the threats and attacks that land and environmental defenders and their communities face. It strives to raise awareness of these abuses and to amplify the voices of defenders in support of their work and their networks.

We define land and environmental defenders as people who take a stand and carry out peaceful action against unjust, discriminatory, corrupt or damaging exploitation of natural resources or the environment.

Land and environmental defenders are a specific type of human rights defender – and are often the most targeted because of their work.

Our definition covers a broad range of people. Defenders often live in communities whose land, health and livelihoods are threatened by the operations of mining, logging, agribusiness or other industries.

Some defend our biodiverse environment. Others support such efforts through their work as human rights or environmental lawyers, politicians, park rangers, journalists, or members of campaigns or civil society organisations.

Global Witness has produced a yearly account of murdered land and environmental defenders since 2012. We document attacks where there is a reasonable and suspected link to an individual’s activism.

Our database also includes forced disappearances of land and environmental defenders where the individual remains missing after at least six months.

We maintain a database of these killings so that there is a record of these crimes, and so we can track trends and highlight the key issues behind them.

Global Witness includes friends, colleagues and the family of murdered land and environmental defenders in its database if: a) they appear to have been murdered as a reprisal for the defender’s work, or b) they were killed in an attack that appears to target a defender.

Research into the killings and enforced disappearances of land and environmental defenders between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2023:

Global Witness identifies killings by reviewing reliable sources of publicly available online information.

- We identify datasets from international and national sources with details of named human rights defenders killed, such as the Front Line Defenders annual report and the Programa Somos Defensores annual report on Colombia. We then research each case.

- We set up search-engine alerts using keywords and conduct other searches online to identify relevant cases.

- As much as possible, we check with in-country or regional partners to gather further information on the cases. We work with 30 local, national and regional organisations in more than 20 countries. We strive to expand our network each year, thus strengthening our data and global coverage.

To meet our criteria, a case must be supported by the following available information:

- Credible, published and current online sources of information.

- Details about the type of act and method of violence, including the date and location.

- Name and biographical information about the victim.

- Clear, proximate and documented connections to an environmental or land issue.

Sometimes we include a case that does not meet all the criteria outlined above if a respected local organisation provides us with compelling evidence that is not available online, based on their own investigations.

Our data on killings is likely to be an underestimate, given that many murders go unreported, particularly in rural areas and in certain countries.

Our criteria cannot always be met by a review of public information such as newspaper reports or legal documents, or through local contacts.

We are aware that our methodology means our figures do not represent the full scale of the problem, and we are constantly working to improve this.

Global Witness’ dataset is reviewed and updated annually. This includes adding, reviewing or disqualifying historical cases if new information comes to light.

In summary, the figures presented in this report should be considered as only a partial picture of the extent of killings of land and environmental defenders across the world in 2023.

We identified relevant cases in 18 countries in 2023, but it is likely that attacks affecting land and environmental defenders also occurred in other countries where human rights violations are widespread.

Reasons why we may not have been able to document such cases in line with our methodology and criteria include:

- Limited presence of civil society organisations, NGOs and other groups monitoring the situation.

- Government suppression of the media and other information outlets.

- Wider conflicts and/or political violence, including between communities, that make it difficult to identify specific cases.